Vulval Pain - Could It Be Vulvodynia?

Vulvodynia is a chronic pain condition affecting 8-16% of women at some point in their lives1. People with vulvodynia experience pain, burning or discomfort in the vulval area, which can include the inner and outer labia (lips) of the vagina, the clitoris, the opening of the vagina and its glands, the opening of the urethra, and the pubic area. Vulvodynia is the most common cause of painful sex prior to pre-menopause1 and has a profound impact on the quality of life of those impacted.

Despite it being so common, it remains poorly understood and is often misdiagnosed and mismanaged. However, recent advances in pain science and our understanding of the role of the brain and nervous system have led to improved methods of assessment, diagnosis and management of this debilitating condition.1

Recent high-quality evidence supports physiotherapy as an effective first-line treatment for vulvodynia. A 2021 randomised controlled trial comparing physiotherapy2 to other treatment for vulvodynia found physiotherapy significantly more effective for:

- Reducing pain intensity during intercourse

- Improving sexual function

- Decreasing sexual distress

- Enhancing patient satisfaction

Symptoms of Vulvodynia

The symptoms of vulvodynia include pain, burning or discomfort in the vulva which cannot be linked to a specific cause. There are two main types of vulvodynia3:

- Provoked vulvodynia is when symptoms occur with touch or pressure to the vulva with activities that should not normally be painful, such as with light touch, inserting a tampon or sexual arousal, sexual intercourse.

- Generalised vulvodynia is vulvar pain which occurs spontaneously and often can be felt constantly. These symptoms are often exacerbated by any external touch or pressure to the vulva, such as when wearing tight clothing or sitting down.

To be diagnosed with vulvodynia, other causes of vulvar pain that are linked to specific disorders need to be ruled out. Some of these conditions include:

- Infectious conditions: eg recurrent thrush, herpes

- Inflammatory conditions: eg lichen sclerosis

- Neurological conditions: nerve injury or compression

- Trauma to the skin or tissue eg during childbirth

- Post-surgical and post-medical treatment eg chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- Hormonal deficits eg during menopause or postnatal periods

Causes of Vulvodynia – a New Understanding

As with any persistent or chronic pain condition, there are a combination of biological, psychological and social factors that can contribute to vulvodynia. Every person has a unique combination of factors and set of circumstances and how vulvodynia impacts their quality of life is also unique to them. It is crucial that people have their story heard, their symptoms validated and a thorough assessment is performed to ensure all factors are considered and addressed. The following potential factors have been identified in current research1:

Biological Factors:

- Changes in the brain and nervous system that lead to the vulval skin and tissue becoming more sensitive

- Pelvic floor muscles; increased tension, pain and difficulty relaxing

- Genetics

- Changes to the levels of inflammation around the vulva when there has been a history of infections, thrush or tissue trauma, despite treatment and healing of the tissues

- Hormonal changes due to menopause, childbirth and some medications

Psychological Factors4:

Psychological Factors4:

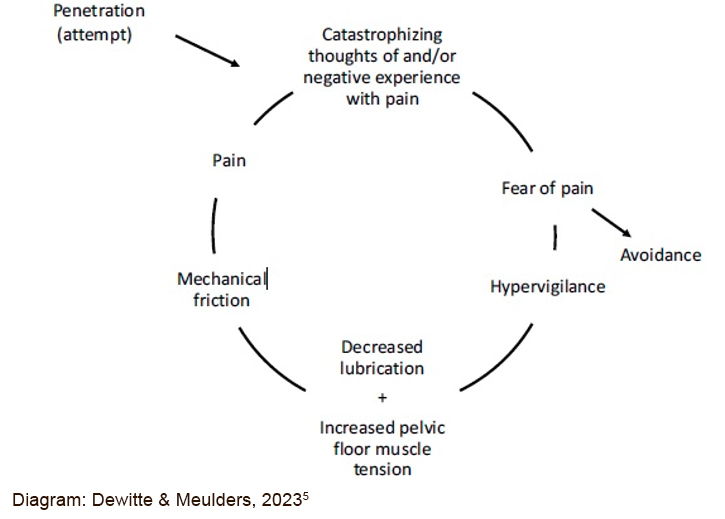

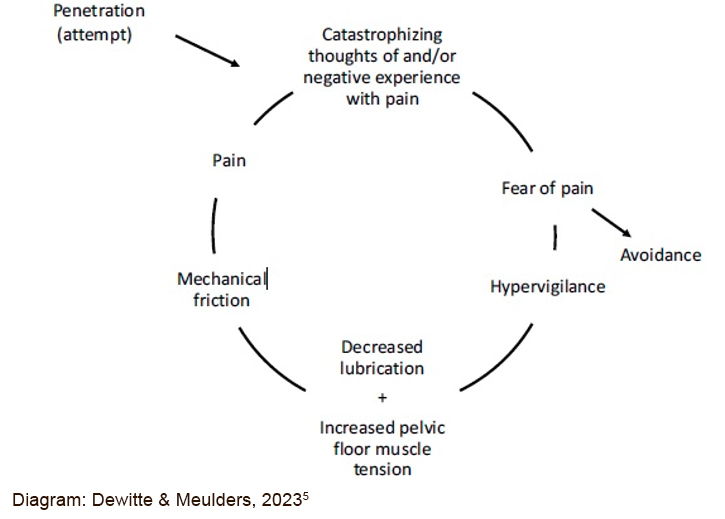

The vulva is a very important and unique part of the body and the brain will prioritise keeping it safe. Experiences of pain and discomfort can lead to:

- Fear of pain

- Worrying the pain will worsen

- Body image concerns

- Reduced arousal and libido

- Sexual anxiety and distress

- Anxiety and depression

Social/Relational/Cultural Factors:

- Impact on intimate relationships

- Partner responses

- Communication difficulties

- Sexual script disruption (a set of ideas, behaviours, and expectations that guide how people think about and act in sexual situations)

- Cultural factors around sexuality

Pelvic Health Physiotherapy Assessment Should Include:

1. Hearing the Story

• Understand the nature of pain & symptoms; history, characteristics & patterns

• Previous investigations and treatments and effect of these

• Impact on emotions, body image, sense of self, relationships and quality of life

2. Assess the Sensitivity of the Nervous System

Physiotherapists have a number of assessment tools that help to understand nervous system sensitivity. This may include questionnaires, identification of other conditions and/or a physical examination that looks for sensitivity with light touch and pressure.

3. Psychological Screening

Thoughts, feelings, beliefs and emotions can play a role in vulvodynia. Understanding the part emotional health is playing can provide invaluable clues to treatment options that may assist. This process often uncovers underlying emotional difficulties that require further assessment with a GP, psychologist, psychiatrist or other mental health professional.

4. Physical Examination

For many with vulvar pain, especially with a history of trauma, a physical and / or a vaginal examination can be scary or worrying. This would only proceed with fully informed consent, be slow and have an option to stop at any time. This would aim to;

• Rule out other conditions

• Assess skin sensitivity

• Assess the pelvic floor muscles – looking for pain, tension, contraction and relaxation and flexibility of the muscles

Research Backed Treatment For Vulvodynia

Research has shown that optimal outcomes are achieved when treatment is individualised and addresses the identified biological, psychological and social factors. It always has the person at the centre and involves shared-decision making1,2,6.

- Multi-Disciplinary Team; in addition to seeing a pelvic health physiotherapist, your GP may also refer you to see a gynaecologist, dermatologist or psychologist. Research shows that vulvodynia is best managed with a team approach, where all treating health professionals communicate with each other regarding care.

- Validation and Hope are an extremely important aspect of care as people with vulvodynia have been frequently told the symptoms are “in their head” and they should simply relax or have a glass of wine for sex to be comfortable. Anyone with these symptoms should feel heard, understood, believed, supported and have hope.

- Establish Meaningful Pelvic Health Goals; for example:

• To be able to comfortably wear leggings to the gym, I would be more motivated to exercise and that’s good for my mental health.

• To be able to insert a tampon so that I can go to the beach in summer when I have my period, so I can socialise with my friends and not feel left out.

• To have comfortable and pleasurable sex with my partner so we can have a more intimate and connected relationship.

- Understanding Pain; learning the how the ‘pain system’ works, including the science of pain, impact on sexuality and sex and sexual health information is a vital component.

- Self-Management strategies such as pain management techniques, appropriate genital skin care and use of lubricants.

- Sexual health education including understanding genital anatomy, libido, arousal and building communication skills and sexual confidence.

- Muscle Relaxation & Breathing; for the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles and breathing practices

- Desensitisation exercises; techniques to reduce the protective response of the muscles and skin and help the body learn that touch is safe.

- Lifestyle Advice including general exercise, sleep, diet and stress management

Vulvodynia Can Be Successfully Treated

Success in treating vulvodynia relies on addressing the complex relationship between the biological, psychological and social contributing factors.

There is strong evidence that supports physiotherapy as an effective first-line treatment, particularly when delivered in conjunction with support from other health care professionals.

If you are suffering in silence with vulvar pain, there is help available. Our physiotherapists at WMHP are highly experienced in the assessment and management of vulvodynia and can support you to achieve your pelvic health goals and improve your quality of life.

References

1. Torres-Cueco R, Nohales-Alfonso F. Vulvodynia-It Is Time to Accept a New Understanding from a Neurobiological Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jun 21;18(12):6639. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126639. PMID: 34205495; PMCID: PMC8296499.

2. Morin, M., Dumoulin, C., Bergeron, S., Mayrand, M. H., Khalifé, S., Waddell, G., ... & Brochu, I. (2021). Multimodal physical therapy versus topical lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: a multicenter, randomized trial. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 224(2), 189-191.

3. Bornstein, J.; Goldstein, A.T.; Stockdale, C.K.; Bergeron, S.; Pukall, C.; Zolnoun, D.; Coady, D.; consensus vulvar pain terminology committee of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD); the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH); the International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS). 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 745–751.

4. Chisari, C., Monajemi, M. B., Scott, W., Moss-Morris, R., & McCracken, L. M. (2021). Psychosocial factors associated with pain and sexual function in women with Vulvodynia: A systematic review. European journal of pain (London, England), 25(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1668

5. Dewitte, M., & Meulders, A. (2023). Fear learning in genital pain: Toward a biopsychosocial, ecologically valid research and treatment model. Journal of Sex Research. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2164242

6. Kaarbø, M. B., Danielsen, K. G., Helgesen, A. L. O., Wojniusz, S., & Haugstad, G. K. (2023). A conceptual model for managing sexual pain with somatocognitive therapy in women with provoked vestibulodynia and implications for physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 39(12), 2539-2552.

December 2024

Psychological Factors4:

Psychological Factors4: