Postnatal Return to Running – A Framework for Health Professionals

As health professionals supporting women following birth, we often find ourselves being asked “when can I return to running – it’s the form of exercise that works best for me.” In the back of our minds is wanting to prevent the occurrence of the statistic we all know well - 1 in 3 women will experience pelvic floor dysfunction after childbirth. So how to do balance these potentially conflicting situations? This challenge has led to women receiving inconsistent and conflicting advice about postpartum exercise. This has not only reduced engagement in physical activity but has left both new mothers and health professionals navigating uncharted territory.

Without national or international guidelines, clinicians often default to generalised recommendations or arbitrary timelines. These approaches fail to address the complex physiological, biomechanical, and psychological changes unique to the postpartum period, leaving women without appropriate, evidence-based support for safely resuming activities like running.

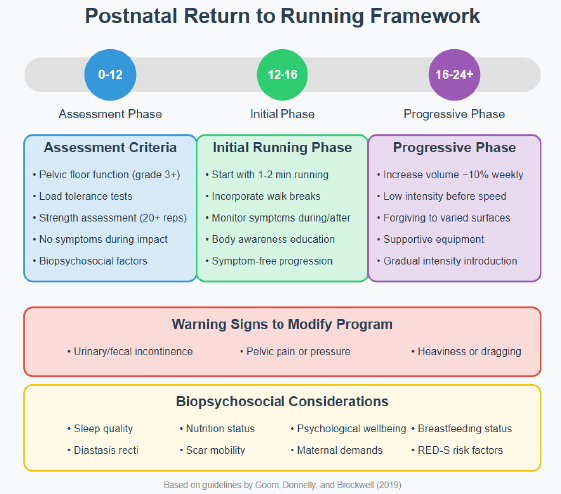

Addressing the large research gap in postpartum exercise, Physiotherapists Tom Goom, Grainne Donnelly and Emma Brockwell1 developed evidence-based guidelines that enhance clinical reasoning for practitioners. These guidelines serve as a foundation for future standardised protocols supporting safe return to running after childbirth.

Addressing the large research gap in postpartum exercise, Physiotherapists Tom Goom, Grainne Donnelly and Emma Brockwell1 developed evidence-based guidelines that enhance clinical reasoning for practitioners. These guidelines serve as a foundation for future standardised protocols supporting safe return to running after childbirth. For those who prefer a quick graphic representation framework, the infographic here summarises the key components of the postnatal return to running framework, including assessment criteria, phased progression, warning signs, and biopsychosocial considerations.

We share the 4 recommendations outlined in the guidelines, the first has level 1A evidence, the other 3 are based on expert opinion and so clearly further research is required.

Recommendation 1: The Need for Individualised Assessment and Rehabilitation

All mothers, regardless of delivery method, should have access to a pelvic health assessment (from 6 weeks postnatal) with a specifically qualified pelvic health / women’s health physiotherapist. This comprehensive evaluation should assess the abdominal wall and pelvic floor, including vaginal and/or anorectal examination as indicated. Screening for signs and symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, as listed below, helps identify issues requiring attention and emphasises the importance of professional assessment and guided rehabilitation.

Validated tools such as the Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire or the Pelvic Floor Bother Questionnaire can effectively screen for pelvic floor dysfunction. Given the high level of evidence supporting pelvic floor muscle training for various conditions, this approach ensures postnatal women benefit from both preventive care and targeted management for pelvic organ prolapse, pelvic floor dysfunction, all types of urinary incontinence, and improved sexual function.

Key signs and symptoms of dysfunction1

- Urinary or faecal incontinence

- Difficult-to-defer urinary or faecal urgency

- Pelvic heaviness, pressure, bulging, or dragging sensations

- Pain during intercourse

- Obstructed defecation

- Pendular abdomen, separated abdominal muscles, or decreased core strength

- Musculoskeletal lumbopelvic pain

Recommendation 2: Return to running is not advisable before 3 months

The physical demands of pregnancy and childbirth significantly transform the body, requiring proper healing before high-impact activities like running can safely resume. Research shows high-impact exercise increases the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction by 4.59 times compared to low-impact alternatives2

Key physiological recovery timelines include:

- Pelvic Floor Structure: The levator hiatus widens during pregnancy and expands significantly after vaginal delivery. While it improves by 12 months postpartum, it rarely returns to pre-pregnancy size. Optimal recovery of the levator ani muscle and supporting tissues occurs by 4-6 months.

- Bladder Support: Bladder neck mobility increases following vaginal delivery and remains higher than pregnancy levels even after recovery.

- Cesarean Recovery: Ultrasound studies reveal the uterine scar remains thickened at 6 weeks, indicating ongoing healing. Abdominal fascia regains only 51-59% of its original strength by 6 weeks, improving to 73-93% by 6-7 months postpartum.

Based on these physiological changes, the body needs ample time to heal and regain strength. It's recommended to engage in low-impact exercises during the first 3 months after childbirth, with a gradual return to running between 3-6 months postpartum at the earliest, and only if no pelvic floor symptoms appear before, during, or after exercise1.

Referral to a pelvic floor specialist is recommended if patients experience:

- Pelvic heaviness/dragging (possible prolapse)

- Urinary leakage or bowel control issues

- Pendular abdomen or midline gap (possible diastasis recti)

- Pelvic/lower back pain

- Abnormal bleeding beyond 8 weeks postpartum

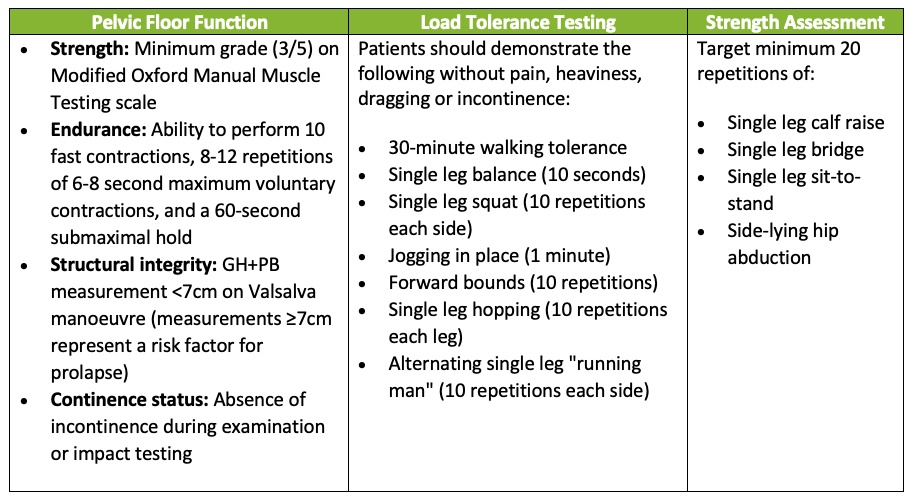

Recommendation 3: Before assessing readiness to run assess your patients pelvic floor health, load management and strength.

While no studies specific to postnatal populations have evaluated exercise readiness, this framework represents best practice by focusing on functional ability rather than arbitrary timelines. Though primarily valuable for pelvic health physiotherapists, these assessment criteria provide useful guidance for all practitioners supporting postpartum women's safe return to high-impact exercise.

Recommendation 4: Whole-Person Considerations

Postpartum women are more than just their pelvic floor and strength metrics. When assessing running readiness, we must consider the whole person. New mothers face unique challenges that impact physical recovery including adapting to motherhood demands, physical demands of breastfeeding as well as the social pressure to quickly regain pre-pregnancy fitness.

A comprehensive biopsychosocial approach should also assess:

- Weight status: BMI >30 increases risk of pelvic floor dysfunction and musculoskeletal injuries.

- Diastasis Recti: Screening for Diastasis Recti Abdominis (DRA), the separation of the outermost abdominal muscles, is recommended by qualified professionals like pelvic health physiotherapists, as DRA can impact abdominal wall function. While research on running with DRA is limited and its relationship with pelvic floor dysfunction remains debated, expert consensus suggests that running before regaining functional control of the abdominal wall may be counterproductive, potentially leading to overloading or compensatory strategies in the pelvic floor.

- Psychological Status: Screen for postnatal depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

- Scar Mobilisation: Consideration of scar mobility and mobilisation is important regardless of delivery method, as both c-section and perineal scars can cause pain and restriction by altering tissue dynamics and potentially affecting adjacent muscles and organs. Scar mobilisation is recommended as good practice since it may reduce inflammation and fibrosis while improving tissue remodelling.

- Breastfeeding Status: Consider potential effects on joint laxity due to hormonal influences, mainly reduced oestrogen levels. Education should be provided about timing of feeds around running, to ensure that the breasts are not overly full or likely to become uncomfortably full during the run.3

- Sleep Quality: Assess for sleep deprivation, which can increass injury risk and recovery.

- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): RED-S refers to impaired physiological functioning caused by inadequate energy intake relative to expenditure, affecting metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, and cardiovascular health. Postnatal women may be particularly vulnerable to RED-S due to breastfeeding demands, social pressure to regain pre-pregnancy fitness, and compromised nutrition, which can impact psychological wellbeing, bone health, pelvic floor function and fertility, requiring education and screening when returning to running. Screen for signs of energy deficit using the RED-S Clinical Assessment Tool.

- Supportive clothing: Okayama et al.4 showed that wearing supportive underwear was nearly as effective as pelvic floor muscle training in reducing stress urinary incontinence in women after a 6-week trial. Further high-quality studies are needed to assess how each intervention compares over a longer period beyond 6 weeks.

Moving Forward

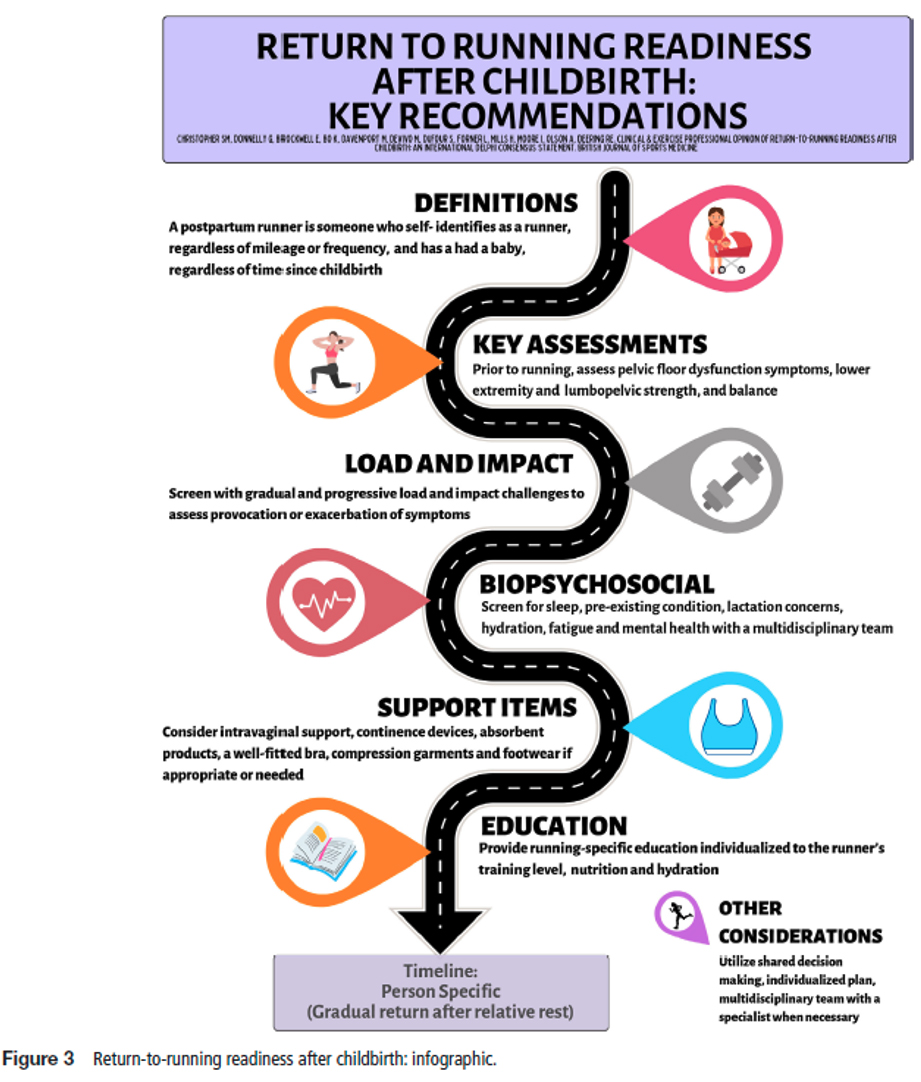

This framework serves as a valuable tool for healthcare professionals to understand the unique post-natal considerations when returning to running, promoting a proactive approach to postnatal care. In 2020 the same group published a lovely info-graphic to share this information in an easy to read digestible format.5

Published in 20246, a 3 round Delphi approach was used to gain international consensus from clinicians and exercise professionals on run-readiness postpartum. Their aim was to define the current practice of determining postpartum run-readiness through a consensus survey of international clinicians and exercise professionals in postpartum exercise to assist clinicians and inform sport policy changes. This group also published a useful inforgraphic summarising their findings.

References

1. Goom, Donnelly, and Brockwell, (2019) Returning to running postnatal – guidelines for medical, health and fitness professionals managing this population DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.35256.90880/2

2. De Mattos Lourenco T, Matsuoka P, Baracat C, Haddad J (2018) Urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal

3. ACOG (2002) Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 267. Obstet Gynecol. 99(1), 171–173.

4. Okayama, H., Ninomiya, S., Naito, K., Endos, Y. and Morikawa, S. (2019) Effects of wearing supportive underwear versus pelvic floor muscle training or no treatment in women with symptoms of stress urinary incontinence: an assessor-blinded randomized control trial. Int Urogynecol J https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-03855-z

5. Donnelly, G, Rankin, Mills, H, DE VIVO, M, Goom, T, Brockwell, E; (2020) Infographic. Guidance for medical, health and fitness professionals to support women in returning to running postnatally. Br J Sports Med, Vol 54 No 18

6. Christopher SM, et al. (2024) Clinical and exercise professional opinion of return to running readiness after childbirth: an international Delphi study and consensus statement. Br J Sports Med; 58:299–312. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2023-107489