Trauma Informed Care In Pelvic Health

Trauma, neglect and attachment disorders are common and create behavioural, physiological and cognitive adaptations that impact daily function and health via the effects on the neurological, endocrine and immune systems. The experience of trauma can result in loss of trust, feelings of guilt and shame, a decreased sense of safety and loss of hope for the future. These changes can affect the way people approach potentially helpful relationships and make it harder for them to engage with health care practitioners.

A Universal Precaution

There is increasing awareness regarding the prevalence of trauma and the significant impact it has on general health and pelvic health. Given the high rates of adversity experienced by children and families, it is now acknowledged that applying trauma informed care (TIC) should be considered a universal precaution rather than an add-on to usual care.

Trauma is frequently associated with bladder and bowel dysfunction and pelvic and sexual pain. It is therefore particularly necessity that practitioners and organisations providing services in pelvic health integrate an understanding of trauma and its impact into all policies, procedures and interactions. Over many years, Women’s & Men’s Health Physiotherapy (WMHP) have developed a trauma informed care framework that supports us to integrate the TIC principles. Our ultimate aim is that our patients feel physically and emotionally safe and empowered to change and our WMHP Physiotherapists feel safe and empowered to facilitate change.

What is Trauma?

Blue Knot, an organisation committed to empowering recovery from complex trauma define trauma as a state of high arousal. It is an event or events in which a person is threatened or feels threatened. The experience of trauma overwhelms the person’s capacity to cope1.

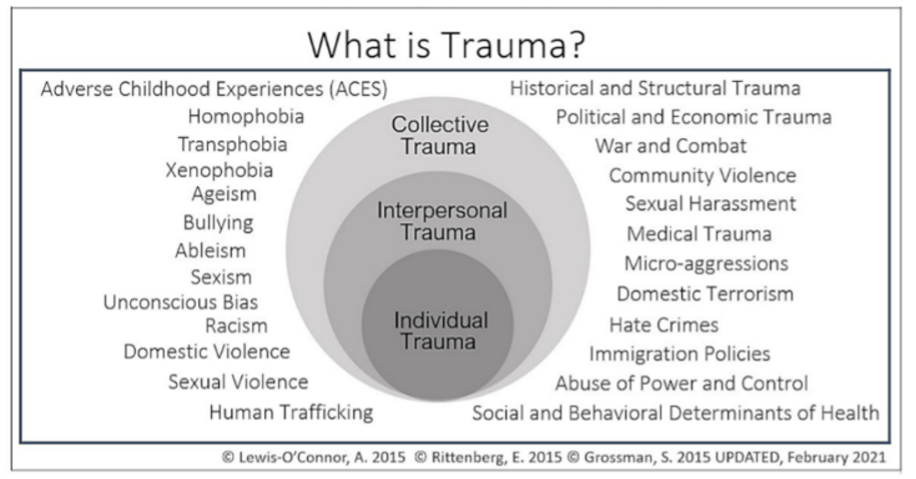

As depicted in this diagram2, trauma can occur as intersectional and dynamic layers. It can be individual resulting from an event or set of circumstances, experienced on an interpersonal level such as adverse childhood events, domestic and sexual violence. Finally, it can occur at a collective level such as cultural, social and political traumas that communities experience across generations.

Trauma Is Prevalent

In 2009, it was estimated that 75% of Australian adults had experienced a traumatic event at some point in their lifetime (Productivity Commission estimates using ABS 2009). In 2023 media releases, The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that 41% of Australians had experienced violence (physical and/or sexual) since the age of 15, 21% had experienced violence, emotional abuse or economic abuse by a partner, 18% of women had experienced sexual violence since the age of 15 and 16% of women were physically or sexually abused before the age of 15.3

What Is Trauma Informed Care?

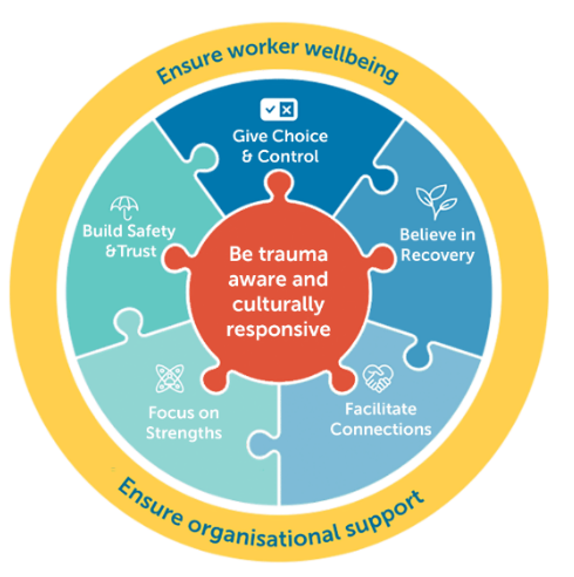

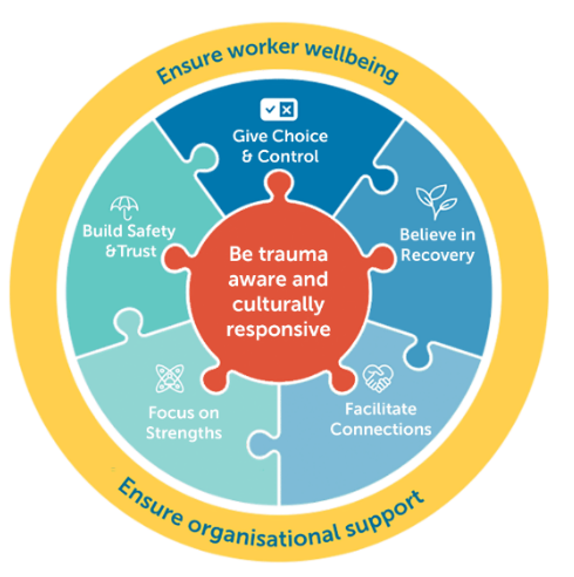

Trauma can leave individuals feeling unsafe, untrusting, powerless, devalued and disconnected. TIC is designed to ensure that service provision does not reinforce these beliefs. Summarised perfectly by this infographic from Phoenix Australia, TIC aims to achieve this by including practices that are based on an understanding of trauma and its impacts. It focusses on strengths and highlights the importance of relationships that build safety and trust, giving choice and control, facilitating connections and conveying hope for recovery4.

TIC rests on the foundation principle of ‘do no harm’. It does not require clinical knowledge and is not ‘treatment’. TIC understands the effects of stress on the brain and body, considers what has happened to the person rather than what is wrong with the person and sees symptoms as the result of coping strategies. It considers the way in which a service is delivered and not just what the service is1. TIC also recognises that health care practitioners themselves may experience trauma and distress related to interactions with patients or may be affected by vicarious trauma.

The WMHP approach as a trauma informed organisation has included intentional application of the principles of TIC, the development of TIC policies and procedures, tools and resources to support crisis and distress management and training for both physiotherapists and administrative personnel, thus supporting the wellbeing and safety of the WMHP team as well as our patients.

Our approach considers the “four R’s” ; TIC assumptions documented a decade ago by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration;5

- Realise the widespread impact of trauma

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of trauma

- Respond by integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures & practices

- Resist re-traumatisation by consciously applying a trauma sensitive lens

Realise The Impact Of Trauma On Pelvic Health

“Trauma is much more than a story about something that happened long ago,” wrote Dr. Bessel van der Kolk in his landmark book, The Body Keeps The Score, “The emotions and physical sensations that were imprinted during the trauma are experienced not as memories but as disruptive physical reactions in the present.”6

Exposure to abuse, violence and chronic, unrelieved emotional stress leads to overstimulation of the normal hormonal response to stress - the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis - keeping the body and nervous system on high alert and moulding a body that gets stuck in fight, flight and freeze. Trauma interferes with the brain circuits that involve focusing, flexibility and being able to stay in emotional control and wreaks havoc on the immune system and functioning of the body’s organs.6

The reminder above of the physiology of trauma means it comes as no surprise that it is predictive of the development of many pelvic health conditions. In a fascinating 2001 study by van der Velde et al

7, women with and without vaginismus demonstrated increased muscle activity of the pelvic floor muscles and trapezius muscles when exposed to threatening and sexually threatening videos. They concluded that

pelvic floor activity is a general protective defence mechanism responding to the brain prioritising protection of the vital reproductive and elimination organs that reside in the pelvis. We have explored the impact of

increased tension of the pelvic floor on pelvic health in a previous blog article. This was further confirmed by a 2021 systematic review that reported a significant relationship between a history of sexual and emotional abuse and the diagnosis of vaginismus and between sexual abuse and dyspareunia

8.

Further sobering evidence-based statistics highlighting the prevalence of trauma in pelvic health conditions include;

- In a sample of 713 women with chronic pelvic pain, 46.8% reported a history of physical or sexual abuse and 31.3% had a positive screen for PTSD.

- Having experienced bullying or abuse is predictive of increased pelvic floor distress, urological symptoms, pain and dyspareunia compared to those who haven’t.

- 44% of people with gastrointestinal disorders reported sexual or physical abuse in childhood or later in life.

- 42% of people with interstitial cystitis / bladder pain syndrome have PTSD.

Recognise Trauma Signs & Symptoms In Pelvic Health

Knowing how widespread trauma is, it should be considered as a potential factor in every pelvic health patient we see and it is therefore vital that we are able to recognise signs and symptoms. Using carefully worded language and providing a safe and empathetic space to allow people to tell their story helps clinicians build awareness of underlying trauma. This doesn’t necessarily mean asking explicit questions about trauma but involves active listening and recognising what our patient’s body may be telling us.

Traumatic memory is encoded as sensory fragments eg visual images, smells, sounds, tastes or touch. These memories are disassociated from normal memory networks and easily triggered by sensory input or by a person, place or situation. This can elicit an intense and unexpected mind and body response as though the trauma is happening in the here and now. This can present as behaviours such as panic, increased muscle tension, flushed blotchy skin, sweating, not maintaining eye contact or looking absent. It can also present as vague symptoms like multimorbidity, chronic pain, hypervigilance, hopelessness and relational distress. Not being engaged in the treatment plan and coping behaviours such as smoking, substance abuse and overeating may also be related to a trauma history.

A 2022 systematic review found a significant association between the number of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and period pain and that sexual abuse and resultant PTSD were the ACE’s most strongly associated with pelvic pain, period pain and pain with sex

9. At WMHP we include the

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Questionnaire10 in a suite of optional psychosocial screening questionnaires to assist our assessment of nervous system and pain system sensitivity. We find the ACE questionnaire provides an invaluable opportunity for patients to reflect on the impact early life experiences may be having on their pelvic health concerns and initiates a conversation about referral to a health professional trained in trauma counselling. Other ways we frame a broad trauma question is “Have you had any life experiences that you feel have impacted your health and wellbeing?”

3

Responding To Disclosures Of Trauma

Health care professionals often report feeling uncomfortable about asking questions about trauma for fear of opening Pandora’s Box11, where they do not have the time, nor the skills and knowledge to respond to the answers appropriately. The ACE study highlights that simply acknowledging the trauma, and listening with empathy to the patient’s story can have a profound impact on their health.10 These conversations can also act as a helpful tool to encourage follow up with a psychologist, when the patient feels ready.

Safety is the overarching priority in both assessment and management when a patient has disclosed trauma. This includes optimising safety in the patient’s environment, relationships, intrapersonal experiences, body and meaning and careful boundary-setting that facilitates choice and empowerment. A key impact of trauma is dysregulation of biological stress modulation, so health professionals should maintain awareness of physiological arousal and support patients to self-regulate. This may utilise bottom up approaches such as sensorimotor grounding, rhythm and movement or top-down approaches such as the use of story, dialogue, ritual and metaphor. This helps to balance input from both the rational mind and the sensory or emotional body, often referred to as the ‘window of tolerance’10.

Therapeutic relationships are also an important part of physiological soothing – they offer an alternative for those who may have lived their developmental years in chronic arousal. Presenting ourselves as a co-regulation resource for patients can be incredibly powerful. This involves self-awareness and self-care, seeking of permission, showing up with curiosity and acknowledging that whilst we may have expert skills, we are not the expert on our patient’s experience.

Resist Re-Traumatisation

A trauma informed approach also includes building trust and mutual respect, protecting privacy and obtaining informed consent throughout the entire consultation. We can resist re-traumatisation by actively and consciously applying a trauma sensitive lens to our conversations and practices, especially through a carefully conducted physical examination.

In her wonderful book, Healing Pelvic Pain9, Dr Peta Wright included a quote (p 142) reflecting on the effects of childhood trauma; “Human brains work better when they are allowed to develop in a safe and nurturing environment, and human bodies experience less pain when they are allowed to receive input from a healthy brain. When we insist on approaching chronic pain as a purely biomedical phenomenon, we consign the patient to suboptimal treatment. That is not acceptable. They were mistreated once as children; there is no excuse for history to repeat itself when they become patients”. This is a poignant reminder of why trauma informed care as a foundation principle of a biopsychosocial approach to pelvic health should be the standard of care.

An important question that we routinely ask as part of obtaining informed consent for an intimate examination is “is there anything in your past that may make this examination uncomfortable or difficult for you?” Obtaining informed consent includes an explanation of all of the assessment options, the purpose, including the option of no assessment. Once a patient feels ready to consent to an assessment, it is important to explain to a patient when you need to touch them and why, remaining at eye level with the patient, obtaining consent at all stages and asking for input regarding how they are feeling throughout the assessment including the opportunity for the patient to stop the assessment at any time12.

Maintaining eye contact and watching body language is also important. For some, an intimate examination can trigger a state of shock or a freeze state, where they can no longer communicate with words. Reminding them that they can use another gesture can be a sign to the clinician that they need to stop the assessment12.

The use of grounding strategies and breathwork can also be an extremely helpful during any examination, as well as a treatment option. To read more about the impact of breathwork on pelvic health, read our article:

Breathe For Your Pelvic Health.

Call To Action

We encourage all health professionals to apply a trauma informed and trauma sensitive lens and framework to patient care. An editorial published in the Australian Journal of Physiotherapy in 202113 highlighted that there is a strong need for;

- good screening of sexual assault history and subsequent psychological illness in women;

- a requirement for future research to provide more detailed approaches to delivering trauma-informed pelvic healthcare to women who are survivors of sexual assault

- competency-based training for physiotherapists so that they can deal with the issues that may arise from screening.

We also acknowledge the impact that a trauma informed approach can have on the clinicians themselves. Su, 202011 recommends personal care and self-compassion to support wellbeing, including personal reflection, which could include mentor or peer support groups. Adopting a trauma informed care approach can appear daunting at first, but with empathy, careful communication, good support amongst clinicians and a strong referral network it is achievable.

References

2. Grossman S, Cooper Z, Buxton H, et al. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2021; 6:e000815.

4. Phoenix Australia, Trauma Informed Care course, 2024

7. Van der Velde J, Laan E and Everaerd W. Vaginismus, a Component of a General Defensive Reaction. An Investigation of Pelvic Floor Muscle Activity during Exposure to Emotion-Inducing Film Excerpts in Women with and without Vaginismus, Int Urogynecol J (2001) 12:328–331

8. S. Tetik & OY.Alkar, Vaginismus, Dyspareunia, and Abuse History: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2021;18:1555−1570.

9. Moussaoui and Grover. The association between childhood adversity and risk of dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain and dyspareunia in adolescent and young adults; a systematic review. Journal of Paediatric and adolescent Gynaecology, Vol 35, No 5, 2022, pp 567-74 in Wright, Peta. Healing Pelvic Pain, Pan Macmillan Australia, 2023.

10. Felitti, VJ, et al. 1998. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

11. Su WM and Stone L. Adult Survivors of Childhood Trauma. AJGP. 2020; 49 (7), 423-430

12. Gorfinkel I Perlow E Macdonald The trauma informed- informed gynaecologic examination CMAJ 2021 Jul 19; 193 doi 10.1503/cmaj.210331 PMID 34281967

13. Stirling J, Chalmers J and Chipchase L. The role of the physiotherapist in treating survivors of sexual assault. J Physio. 2021; 67(1), 1-2.

Further resources can be obtained at:

- Blue Knot Foundation

- Pheonix Australia

- RACGP