A Paradigm Shift In Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain

- Stable: The pelvis is resilient and adaptable to the demands of pregnancy, childbirth and childcare while maintaining its stable structure.

- Safe: Postural and pelvic structural changes are normal, safe and necessary to support the growing demands of pregnancy and childbirth.

- Self Manageable: Pain education, emotional wellbeing, sleep optimization, exercise and external supports that promote independence are the most helpful strategies to reduce pelvic girdle pain.

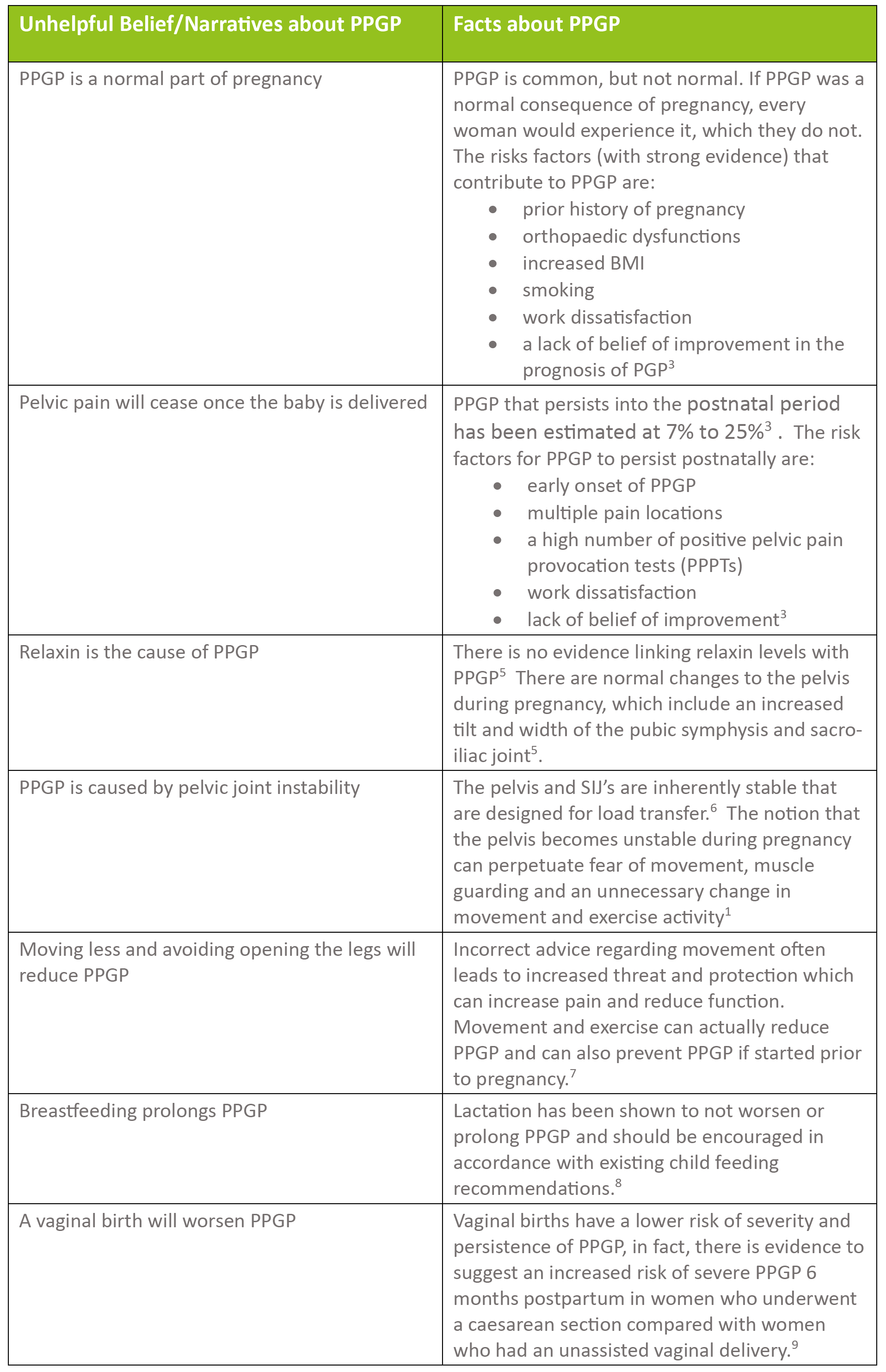

1. Beales D, Slater H, Palsson T, O’Sullivan P. Understanding and managing pelvic girdle pain from a person-centred biopsychosocial perspective Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 2020; 48:102-152

2. Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(6):794–819.

3. Clinton S, Newell A, Downey P, Ferreira K. Clinical Practice Guidelines Pelvic Girdle Pain in the Antepartum Population: Physical Therapy Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health From the Section on Women's Healthand the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2017; ¬ 41(2)¬ p 102–125

4. Pulsifer J, Britnell S, Sim A, et al. Reframing beliefs and instiling facts for contemporary management of pregnancy- related pelvic girdle pain Br J Sports Med 2022;0:1–2. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-105724

5. Aldabe D, Ribeiro DC, Milosavljevic S and Bussy MD. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and its relationship with relaxin levels during pregnancy: a systematic review Eur Spine J. 2012 Sep;21(9):1769-76.

6. Snijders CJ, Vleeming, and Stoeckart R. Transfer of lumbosacral load to iliac bones and legs: Part 1: Biomechanics of self-bracing of the sacroiliac joints and its significance for treatment and exercise. Clinical Biomechanics. 1993; 8(6):285-294

7. Margie H Davenport MH, Andree-Anne Marchand A-A, Michelle F Mottola MF, Veronica J Poitras VJ, Casey E Gray CE, Alejandra Jaramillo Garcia AJ et al. Exercise for the prevention and treatment of low back, pelvic girdle and lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(2):90-98. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099400.

8. Bjelland EK, Owe KM, Stuge B, Vangen S and Eberhard-Gran M. Breastfeeding and pelvic girdle pain: a follow-up study of 10,603 women 18 months after delivery. BJOG. 2015;122(13):1765-71

9. Bjelland EK, Stuge B, Vangen S, et al. Mode of delivery and persistence of pelvic girdle syndrome 6 months postpartum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Apr;208(4):298.e1-

September 2023