Looking Outside The Pelvis In Persistent Pelvic Pain

According to the 2022 European Association of Urology Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain, Persistent Pelvic Pain (PPP) is persistent pain perceived in structures related to the pelvis of either men or women1. PPP can be further categorised as Chronic Primary Pelvic Pain, where there is no obvious pathology and Chronic Secondary Pelvic Pain, where there is specific disease or pathology associated pelvic pain1. For both categories, pain must have been continuous or recurrent for at least 3 months or have been in a cyclical pattern for at least 6 months.

PPP is associated with negative cognitive, behavioural, sexual and emotional consequences as well as with symptoms suggestive of lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel, pelvic floor or gynaecological dysfunction2. PPP conditions are complex in nature because they are often caused by and contribute to dysfunction in one or more of the gynaecological, urological, gastrointestinal, neurological, musculoskeletal, and psychological systems1.

To achieve positive outcomes for those suffering with PPP, clinicians need to have a strong understanding of the pain system in general. This leads to effective assessment, classification and phenotyping of pain presentations, application of interventions which are person centred and follow principles of best practice precision medicine.

Definition of Pain

It is important when exploring pelvic pain that we reflect on the contemporary understanding of pain. In 2020 the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) updated their definition of pain;

An unpleasant sensory AND emotional experience associated with, or resembling

that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage2.

They then outlined 5 key considerations;

- Pain is always a personal experience that is influenced to varying degrees by biological, psychological, and social factors.

- Pain and nociception are different phenomena. Pain cannot be inferred solely from activity in sensory neurons.

- Through their life experiences, individuals learn the concept of pain.

- A person’s report of an experience as pain should be respected.

- Although pain usually serves an adaptive role, it may have adverse effects on function and social and psychological well-being.

This definition and key considerations highlight that a variety of factors will influence an individual’s pain experience, which is why WMHP is committed to utilising a biopsychosocial framework for assessment and treatment of people with persistent pelvic and sexual pain.

Classifications of Pain

The IASP also released a set of clinical criteria that classifies pain into 3 main subtypes2:

Nociceptive Pain: Pain that arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to the activation of nociceptors.

Eg Pain around an episiotomy site in the early post-natal period

Neuropathic Pain: Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system.

Eg Pudendal neuralgia

Nociplastic Pain: Pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence of disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain.

Eg Provoked or Unprovoked Vulvodynia, Bladder pain syndrome, Endometriosis-Associated Pain, Persistent Pelvic Pain (Primary/Secondary)

Mixed Pain: Pain arising from a combination of the above classifications3.

Why Phenotyping Pain Is A Key Factor In Providing Precision Medicine

Both Primary and Secondary Persistent Pelvic Pain presentations are often nociplastic in nature.

There may also be nociceptive components eg if the presence of endometrial lesions is identified, or if thrush has been confirmed for someone with vulvodynia. Sometimes pain persists despite the nociceptive driver being addressed, eg pain continuing after adequate surgery and hormonal suppression for endometriosis, or vulvodynia symptoms persisting after the infection has been appropriately treated. This may indicate the pain is more nociplastic in nature. It is important to assess for the presence of nociplastic pain, as poor outcomes are common due to both conservative and surgical treatments targeting a presumed source of nociception3.

Clinical Identification of Suspected Nociplastic Pain

There are a number of tools and methods available to identify possible nociplastic pain.

Central Sensitisation Inventory:

The Central Sensitisation Inventory (CSI) is a questionnaire validated in the chronic pain population that has also been studied to help identify nociplastic pain in endometriosis4. A score ≥ 40 on Part A or 1 or more of the conditions in Part B is strongly correlated with central or nociplastic mechanisms.

Clinical Examination:

Two of the hallmark features of nociplastic pain are allodynia and hyperalgesia:

• Allodynia: Pain due to a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain2. In PPP, one of the tests for allodynia is a Cotton Swab Test (Q-tip test) as well as palpation.

• Hyperalgesia: Increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain2.

Other indicators that suggest Nociplastic Pain:

• Diffuse, widespread pain

• Increased sensitivity to sound and/or light and/or odours

• Sleep disturbance with frequent nocturnal awakenings

• Fatigue

• Cognitive problems such as difficulty with focus and attention, memory disturbances

• Pain modulated by nervous system processing via the following factors; stress, nutrition, sleep, physical activity, cognitions, threatening experiences.

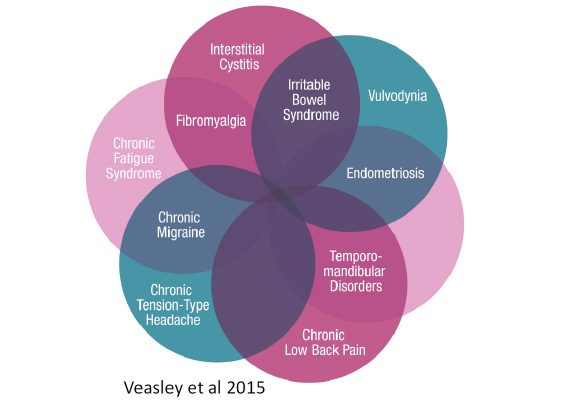

Nociplastic pain is also commonly associated with overlapping conditions in the pelvis, which Veasley et al in 2015 highlighted in this graphic. Interestingly, many of the overlapping conditions are located in the pelvis. The presence of any of these conditions may indicate nociplastic pain at play.

Psychosocial Assessment for PPP

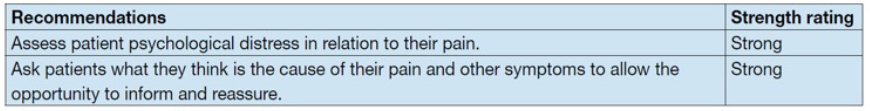

EAU guideline strong recommendation2 around the importance of psychological distress.

Whilst we ensure the use of objective tests with our biological assessment, too often health professionals make assumptions regarding a persons’ emotional state without accurately having assessed it. The emotional and psychological burden on the individual is significant, with PPP shown to be associated with depression, anxiety, fatigue, poorer quality of life, difficulty performing activities of daily living, relationship breakdown, sexual dysfunction, and feelings of isolation, hopelessness, and worthlessness.

For this reason, the 2022 European Association of Urology guidelines for PPP recommend early assessment of the associated cognitive, behavioural, and emotional factors so that appropriate models of care can be provided to individuals2 . There are many well-established and validated screening questionnaires available that assess psychological factors in people with persistent pain but not many of these questionnaires have been specifically designed or tested in the PPP population5.

As part of a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment of nociplastic pain and central modulation, all WMHP Pelvic Health Physiotherapists have been inviting our patients to complete a suite of 11 psychosocial screening questionnaires (that also includes the Insomnia Severity Index and Adverse Childhood Experiences) with all of our PPP patients and others with a sensitised nervous system. We have found patients to be very open to completing these screening tools as they help us to remove any judgement or use of “intuition” around the emotions, thoughts and beliefs that they may have. We use the results of these questionnaires not to diagnose mental health conditions but to help us and our patients have a greater understanding of the factors contributing to their symptoms and to individualise shared decision making around treatment choices. It helps us not just target the tissues with bottom up strategies but to incorporate top down strategies such as pain education, sensory-motor rich exercises, stress management, sleep training and communication skills. It has been our experience that this approach has a significantly positive impact on outcome and achievement of pelvic health goals.

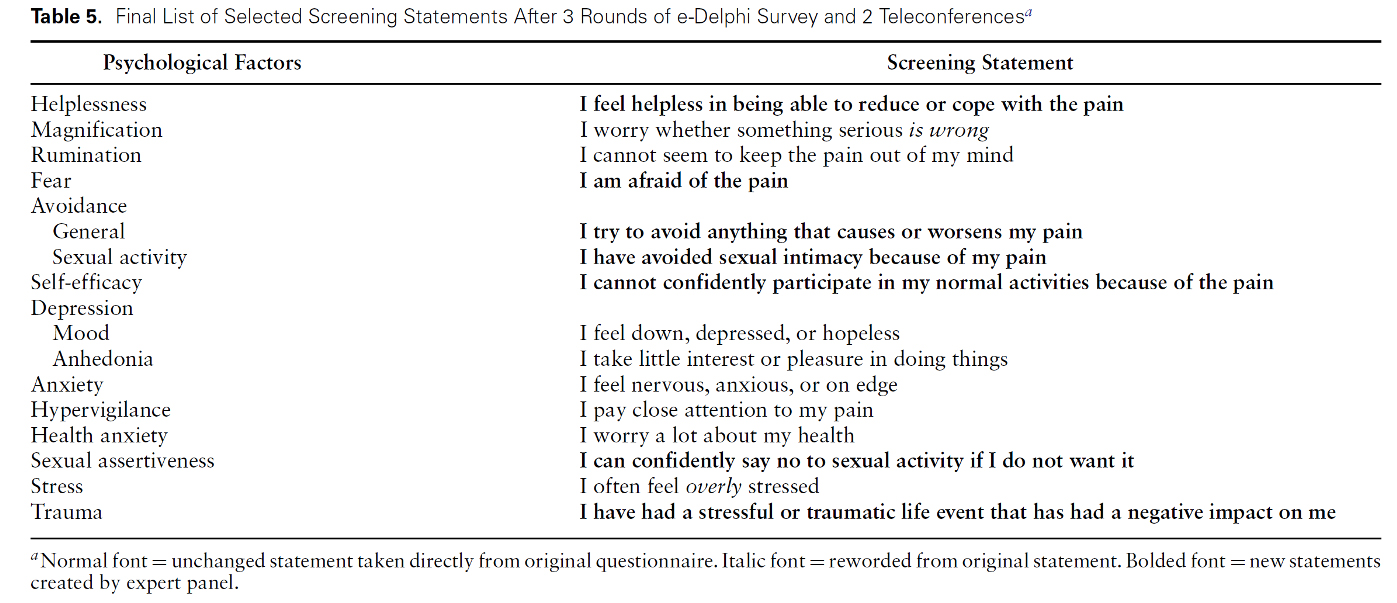

3PSQ – A Novel Tool To Assess For Psychological Factors in PPP

In the first study to investigate which psychological factors are the most appropriate to screen for in those with PPP, a group of Health Practitioners from WA, NSW and SA aimed to develop a concise questionnaire.5 They hoped the 3PSQ would encourage increased utilisation by clinicians, be user-friendly for patients and specifically target relevant psychological factors in the PPP population5. Through an e-Delphi process, they determined which psychological factors should be included and using validated questionnaires, agreed on the most appropriate statement for each factor.5 The final list of statements and what they assess from a psychosocial perspective are included in the table below.

How Can the 3PSQ Help Clinicians?

Anxiety, depression and stress are known to be more prevalent in people with PPP and we see a link between stress and pain-modulating systems, contributing further to persistent pain. Increased levels of health anxiety lead to avoidance, hypervigilance and safety-seeking behaviours. Higher rates of physical and sexual abuse and other trauma are also found in women with PPP5.

All of these psychological comorbidities influence recovery and response to treatment – negatively and positively. Low mood, worry and stress can dysregulate neuromodulation of pain, impact pain perception and the ability to cope with pain. In turn this can lead to increased pain severity and health care utilisation and decreased physical functioning, coping strategies and outcomes.

The good news is, once identified, these psychological factors are potentially modifiable, many within the scope of non-psychologists. Having this specific knowledge can help patients make sense of their pain, encourage them to seek formal Psychological support and engage in exercise and movement practices that improve mood and reduce stress. The new 3PSQ screening tool is available to download on our website and please contact us if you would like to learn more about using this tool with your patients.

A Call to Action

Traditionally persistent pelvic and sexual pain has been treated by Physiotherapists with manual therapy and pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques. However, it is well-established that best practice utilises a biopsychosocial framework, especially when central pain mechanisms and a hypersensitive pain system are present. There are a number of evidence-based treatment options for anxiety, depression and psychological trauma such as cardiovascular and resistance exercise.

Pelvic Health Physiotherapists are well placed to practice within a psychologically informed wholistic framework, addressing factors such as sleep, stress and fear of movement. Compelling evidence also exists for the incorporation of pain science education, graded exposure to movement, breathwork, mindfulness, Qi Gong and yoga.

We implore all health professionals supporting people with PPP to embrace a biopsychosocial framework, including a thorough assessment of the biological AND psychosocial contributing factors to enhance patient care and outcomes. Reducing passive therapies and empowering our patients to be active participants in their management improves self-efficacy and outcomes in a number of PPP conditions. Physiotherapists working in this area should upskill in these treatment options. Our recommendation for this is to complete a course through Reframe Rehab.

References

1. Engeler D, Baranowski AP, Borovicka J, et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2022

2. Raja et al 2020 e revised IASP definition of pain: concepts, challenges and compromises, Pain DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.000000000001939

3. Nijs,J.;Lahousse,A.; Kapreli, E.; Bilika, P.; Saraçog ̆lu, I ̇.; Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; De Baets, L.; Leysen, L.; Roose, E.; et al. Nociplastic Pain Criteria or Recognition of Central Sensitization? Pain Phenotyping in the Past, Present and Future. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ jcm10153203

4. Orr N, Wahl KJ, Lisonek M, Joannou A, Joannou A, Noga A et al. Central sensitization inventory in endometriosis. Pain. 2022; 163(2):e234-e245.

5. Pontifexet al (2021) How Might We Screen for Psychological Factors in People with Pelvic Pain? An e-Delphi Study, Physical Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab015

July 2023