Breathe For Pelvic Health

Whilst commonly overlooked, dysfunctional breathing patterns contribute to many pelvic health disorders. In our clinical practice, we regularly screen for and notice altered and suboptimal breathing patterns in people that have pelvic floor muscle (PFM) dysfunction (with increased OR decreased resting muscle tone), persistent pelvic and sexual pain as well as urinary and anorectal dysfunction.

Breathing is often one of the simplest ways that we can influence pelvic floor muscle activity, whether that be to increase awareness and activation of the PFM, or to aid relaxation of the PFM. Additionally, breathing is one of the fastest ways we can influence a person’s state, whether that be physical, mental or emotional. In relation to pelvic health, the impact of this on pelvic pain, urgency symptoms as well as the ease with which people can void and defaecate can be profound.

Breathwork is a term used to describe breathing exercises or breathing practices that are intended to have a therapeutic effect. The wonderful thing about breathwork, is that it is accessible to everyone at any time of the day, regardless of where they are and what they are doing. It doesn’t require any equipment, it doesn’t cost anything and the impact can be immediate.

Breathing and the PFM

An effective breathing pattern requires modulated PFM activity1,2,3. The lungs are actually passive balloons that inflate and deflate based on pressures changes around them in the abdomino-pelvic cavity. The abdomino-pelvic cavity is like a cylinder, with the diaphragm as the lid, the abdominal and lumbar muscles as the walls, and the PFM as the base. These muscle groups work together to modulate intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) during breathing by timing their periods of contraction and relaxation2.

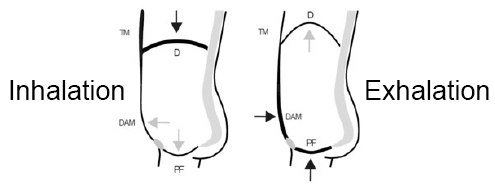

During inhalation, the diaphragm descends, allowing the lungs to expand down and out, whilst the PFM relaxes and descends. During exhalation, the PFM contracts whilst the diaphragm rises2,3, contributing to the air in the lungs being forced out.

Talasz, H et al 2022

D = thoracic diaphragm, PF = pelvic floor, DAM = deep anterolateral abdominal muscles, TM = thoracic muscles. The thicker lines indicate a muscle contraction and the thinner lines indicate a muscle relaxation. The black arrows indicate an active force vector and the grey arrows indicate a passive force transmission.

It is important to note that dysfunctional breathing patterns can be caused by changes in PFM tone AND conversely, altered PFM tone can also cause dysfunctional breathing patterns.

| Dysfunctional Breathing Patterns |  | Altered PFM Tone |

If the PFM have increased resting tone, they may not move downwards during inhalation. This can lead to the diaphragm also not moving downwards and instead, contributing to an apical breathing pattern.

If the PFM have reduced resting tone, they may not contract enough during exhalation, reducing the elevation of the diaphragm.

Breathing and Incontinence

When we cough, sneeze or perform an activity requiring increased IAP, PFM should naturally contract with this forceful expiration to maintain continence. If the amount of IAP is greater than urethral closure pressure created by the PFM and other factors, this can result in stress urinary incontinence. This could occur if the PFM are weak or if the PFM have increased tone.

Breathing: The Remote Control of the ANS

Breathing can act like the remote control of the Autonomic Nervous System

We are all familiar with the role of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the protective effects of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. It is often assumed that these two systems are dichotomous, meaning people are either in one state or the other. However, the systems are more of a continuum. Breathing can act like the remote control of the ANS. When the dial of the remote control is turned towards the sympathetic state, breathing becomes fast, shallow and incomplete. When the dial of the remote control is turned towards the parasympathetic state, breathing is often calm, deep and complete. There are times when activating the sympathetic nervous system is required eg when someone is about to go for a run, attend an important meeting or if they need to escape a dangerous situation. It is not ideal, however, to remain in a sympathetic state for extended periods of time.

We often ask people if they’ve ever noticed that they automatically sigh when they are in pain or feeling stressed or anxious. This is an example of their ANS subconsciously trying to use breathing to move from a sympathetic state towards a parasympathetic state. Just being aware of this happening can alert people to become more aware of their breathing and then take steps to regulate it to a more effective pattern. We teach how to breathe slowly and deeply into the lower part of their lungs, thereby evoking a relaxation response and turning the remote control dial towards the parasympathetic state. This can have an immediate and powerful impact on changing not only their pain experience but their emotional and mental state as well.

Breathing and Persistent Pelvic Pain

We explored earlier the impact of breathing on PFM tone and vice versa. People experiencing persistent pelvic pain (PPP) commonly exhibit increased tone through their abdominal wall and PFM. We also know that PPP is associated with a sensitised nervous system4. The brain is innately protective of the pelvic area, namely due to the vital organs that are housed inside and the sensitive and private nature of these organs. Thus, it is only natural for the brain and body to produce protective responses in the pelvis when the brain has an actual or perceived evidence of danger or threat. Protective responses can come in the form of muscle tension (ie increased PFM or abdominal tone) as well as persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

By utilising breathwork, we can influence not only the ANS by encouraging the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, but we can also influence PFM and abdominal muscle tension to aid relaxation.

Breathing is a very effective top down/bottom up approach to address PPP

Breathing and The Bowel

Effective defaecation dynamics require descent of the diaphragm and widening of the waist as the abdominal wall bulges whilst rectus abdominus and internal/external obliques contract eccentrically. The external anal sphincter and puborectalis also need to relax. This coordinated approach results in enough propulsive force to facilitate defaecation5. We often find that in people that experience obstructed defaecation, incomplete emptying and defaecation dyssnergia they exhibit increased tension in their diaphragm, abdominal muscles and/or PFM. Diaphragmatic breathing regulates the ability of the diaphragm and PFM to descend and relax at the right time and can have a dramatic impact on defaecation dynamics and symptoms5.

Another benefit of diaphragmatic breathing is the massage type effect it can have on the abdominal contents as the diaphragm descends during inhalation. Additionally, we know that calm, deep breathing stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system, triggering the ‘rest and digest’ response in the body.

Breathe For Pelvic Health

Whilst breathwork might seem like an insignificant treatment, it can be one of the most simple and effective strategies to improve pelvic health. It is another tool in our pelvic health toolkit that we successfully use to restore pelvic health, empowering every person to live their best life.

References

1 Hodges PW, Sapsford R and Pengel LHM Postural and Respiratory Functions of the Pelvic Floor Muscles Neurourology and Urodynamics 2007; 26:362–371

2 Talasz, H.; Kremser, C.; Talasz, H.J.; Kofler, M.; Rudisch, A. Breathing, (S)Training and the Pelvic Floor—A Basic Concept. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1035. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/healthcare10061035

3 Aljuraifani R, Stafford RE, Hall LM, van den Hoorn W, Hodges PW. Task-specific differences in respiration-related activation of deep and superficial pelvic floor muscles. J Appl Physiol 2019; 126: 1343–1351.

4 Jo Nijs, Steven Z George, Daniel J Clauw, César Fernández-de-las-Peñas, Eva Kosek, Kelly Ickmans, Josué Fernández-Carnero, Andrea Polli, Eleni Kapreli, Eva Huysmans, Antonio I Cuesta-Vargas, Ramakrishnan Mani, Mari Lundberg, Laurence Leysen, David Rice, Michele Sterling, Michele Curatolo. Central sensitisation in chronic pain conditions: latest discoveries and their potential for precision medicine. The Lancet 2021 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00032-1

5 Rao, SSC and Patcharatrakul T. Diagnosis and Treatment of Dyssynergic Defecation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2016; 22(3) 423-435.

July 2023